Shut The Box

For the holidays this year I received the game Shut The Box. The rules of the game are relatively simple, at the start of the game all tiles are “open”, showing the numbers 1 to 9 inclusive. The player then rolls two dice, and must “close” tile values equal to the number of pips showing on the dice. For example, if the total number of dots is 8, the player may choose any of the following sets of numbers

- 8

- 7, 1

- 6, 2

- 5, 3

- 5, 2, 1

- 4, 3, 1

The player repeats this process unil they cannot satisfy their dice roll with the tiles left on the board. Their score is the sum of values remaining on the “open” tiles. After this the box is handed to the next player, the winner of the round is the player with the fewest points.

There are many variants or extensions described on the Wikipedia page, but this simple version is what I was playing on Christmas day. After playing for a couple of hours while watching Christmas movies I had a couple of questions about the game.

- What is the expected value of a game?

- What is the best opening roll?

- Is it ever in a players’ best interest to not close the largest tile they can?

- What is the value of going second in a two player game?

This is a small enough game that we can explicitly solve it for both the one player and two player cases.

import random

from collections import defaultdict

from itertools import product

import copy

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

%matplotlib inline

# Map from Dice Roll To Probability of it Happening over Two Dice

dice_probs = {}

for d1 in range(1, 7):

for d2 in range(1, 7):

total = d1 + d2

if total not in dice_probs:

dice_probs[total] = 0

dice_probs[total] += 1.0/36.0

# Map From Dice Roll To Possible Tiles to Flip Down

tile_lookup = defaultdict(list)

tiles = tuple([True for x in range(1, 10)])

tile_values = list(range(1,10))

for l in product([0,1], repeat=9):

total = 0

for i, elem in enumerate(l):

total += l[i] * tile_values[i]

if 2 <= total <= 12:

tile_lookup[total].append(l)

def valid_move(move, tiles):

"""

:param move: list of int, tiles to attempt to flip down

:param tiles: list of int, tiles currently on the board

:return: Bool is the move valid for tiles on the board

"""

for i in range(len(move)):

if move[i] == 1 and tiles[i] != 1:

return False

return True

def flip_tiles(move, tiles):

"""

:param move: list of int, tiles to attempt to flip down

:param tiles: list of int, tiles currently on the board

:return: list of int, the new board

"""

retval = []

for i in range(len(move)):

if move[i] == 1:

retval.append(0)

else:

retval.append(tiles[i])

return tuple(retval)

def score_tiles(tiles):

"""

:param tiles: list of int, tiles currently on the board

:return: int the score of the board

"""

total = 0

for i in range(1, 10):

if tiles[i-1] == 1:

total += i

return total

def get_valid_moves(tiles, roll):

"""

:param tiles: list of int, tiles currently on the board

:param roll: int, the roll for the player

:return: list of list of int, legal moves for this board state with this roll

"""

retval = []

for move in tile_lookup[roll]:

if not valid_move(move, tiles):

continue

retval.append(move)

return retval

# Store expected value in [(board_state, roll)] with roll==0 being the player not having rolled yet

memoize = {}

empty_board = tuple([0 for x in range(1,10)])

memoize[(empty_board, 0)] = 0

def dfs(tiles, roll):

if (tiles, roll) in memoize:

return memoize[(tiles, roll)]

if roll == 0:

total = 0

for my_roll, prob in dice_probs.items():

total += dfs(tiles, my_roll) * prob

memoize[(tiles, roll)] = total

return total

best_score = float('inf')

for move in get_valid_moves(tiles, roll):

new_tiles = flip_tiles(move, tiles)

roll_score = dfs(new_tiles, 0)

if roll_score < best_score:

best_score = roll_score

if best_score == float('inf'):

best_score = score_tiles(tiles)

memoize[(tiles, roll)] = best_score

return best_score

full_board = tuple([1 for x in range(1,10)])

dfs(full_board, 0)

Now that we have a calculated optimal value function for the expected value of a game we can answer some of my questions from above. With the exact value function we can loop over actions to find an optimal policy for expected value.

What is the expected value for the game?

print(dfs(full_board, 0))

11.157508444202621

What is the best opening roll?

retval = []

for i in range(2, 13):

retval.append([i, memoize[(full_board, i)]])

retval = sorted(retval, key=lambda x: x[1])

for elem in retval:

print(elem)

[9, 7.6236893875640135]

[8, 9.24080617861096]

[12, 9.936173208638165]

[7, 10.825008858089767]

[10, 11.139918487467915]

[11, 11.194009457452708]

[6, 11.726631321763904]

[5, 12.514746172581951]

[4, 13.706206147751468]

[3, 14.31391370496678]

[2, 15.838927661162352]

The best roll by far is a 9. The worst roll is a 2.

Is it ever in a players’ best interest to not close the largest tile they can?

To answer this question we have to look over all 2**9 possible board states and evaluate if the Greedy move is the same as the best move.

def to_bin(l):

"""

param l: list of int, the board state

return: int the binary representation of the board state

"""

l = l[::-1]

return int("".join([str(x) for x in l]), 2)

exceptions = []

for board_state in product([0,1], repeat=9):

if sum(board_state) == 0:

continue

for roll in range(2, 13):

best_score = float('inf')

best_move = None

for move in get_valid_moves(board_state, roll):

new_tiles = flip_tiles(move, board_state)

roll_score = dfs(new_tiles, 0)

if roll_score < best_score:

best_score = roll_score

best_move = move

if best_score == float('inf'):

continue

biggest_move = max(get_valid_moves(board_state, roll), key=to_bin)

if biggest_move != best_move:

better_option = flip_tiles(best_move, board_state)

greedy_option = flip_tiles(biggest_move, board_state)

exceptions.append([pretty_print_roll(board_state), roll, pretty_print_roll(best_move), dfs(better_option, 0), dfs(greedy_option, 0)])

exceptions = sorted(exceptions, key=lambda x: x[-2] - x[1])

print(f"Number of exceptions: {len(exceptions)}")

df = pd.DataFrame(exceptions[:5])

df.columns = ["Board", 'Roll', 'Best Move', "Expected Value", "Greedy Value"]

df

Number of exceptions: 210

Board Roll Best Move Expected Value Greedy Value

0 1,2,3,4,7, 12 2,3,7, 4.111111 4.214506

1 1,2,3,4,5,6, 12 3,4,5, 4.524691 4.638117

2 1,2,4,5,6, 12 2,4,6, 4.611111 4.763889

3 1,3,4,5,6, 12 3,4,5, 5.000000 5.300926

4 1,2,3,4,6, 11 2,3,6, 4.111111 4.214506

So out of the (10 Dice Rolls) * (512 Tile States) = 5120 game states it is advantageous to not play greedily in 210 circumstances. The largest difference in expected value though from these changes is 0.1 points.

Let’s assume the players are playing without knowledge of each other’s scores and simply play to optimize expected value or to play the greedy move, how big a difference does it make?

def get_move_best(board_state, possible_moves):

best_score = float('inf')

best_move = None

for move in possible_moves:

new_tiles = flip_tiles(move, board_state)

roll_score = dfs(new_tiles, 0)

if roll_score < best_score:

best_score = roll_score

best_move = move

return best_move

def get_move_greedy(board_state, possible_moves):

return max(possible_moves, key=to_bin)

def simulate(method="best"):

my_tiles = tuple([1 for x in range(1,10)])

while True:

d1, d2 = random.randint(1,6), random.randint(1,6)

possible_moves = get_valid_moves(my_tiles, d1+d2)

if len(possible_moves) == 0:

return score_tiles(my_tiles)

if method=='best':

move = get_move_best(my_tiles, possible_moves)

if method=='greedy':

move = get_move_greedy(my_tiles, possible_moves)

my_tiles = flip_tiles(move, my_tiles)

games_played_ev = [simulate() for x in range(10_000)]

games_played_greedy = [simulate(method='greedy') for x in range(10_000)]

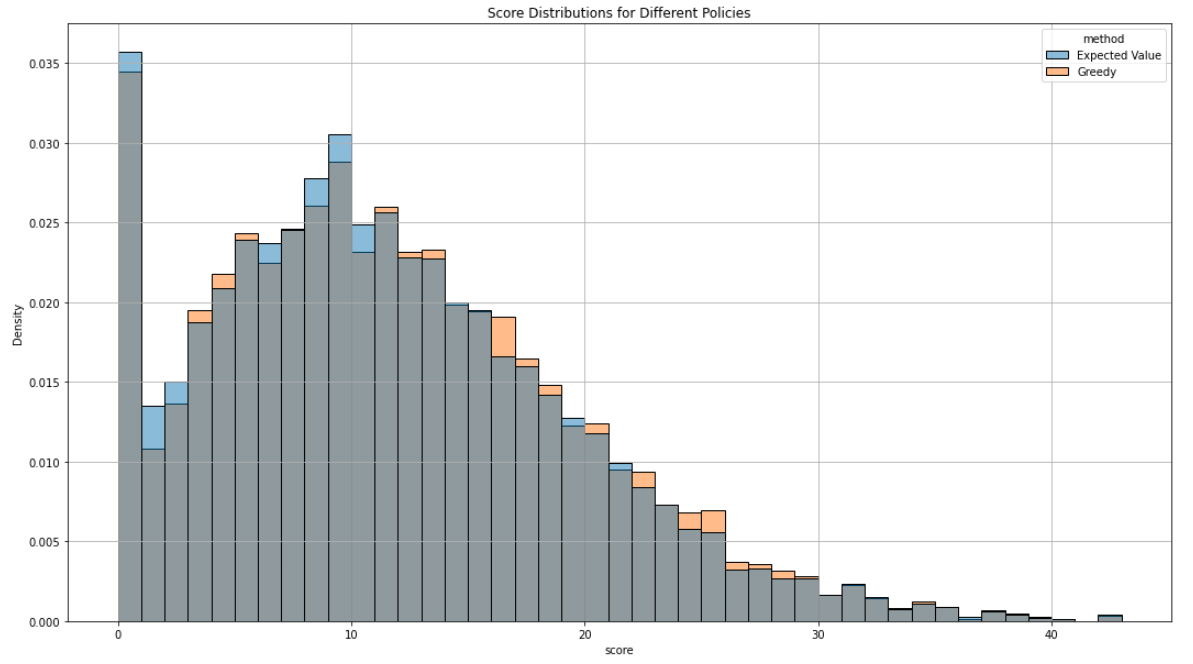

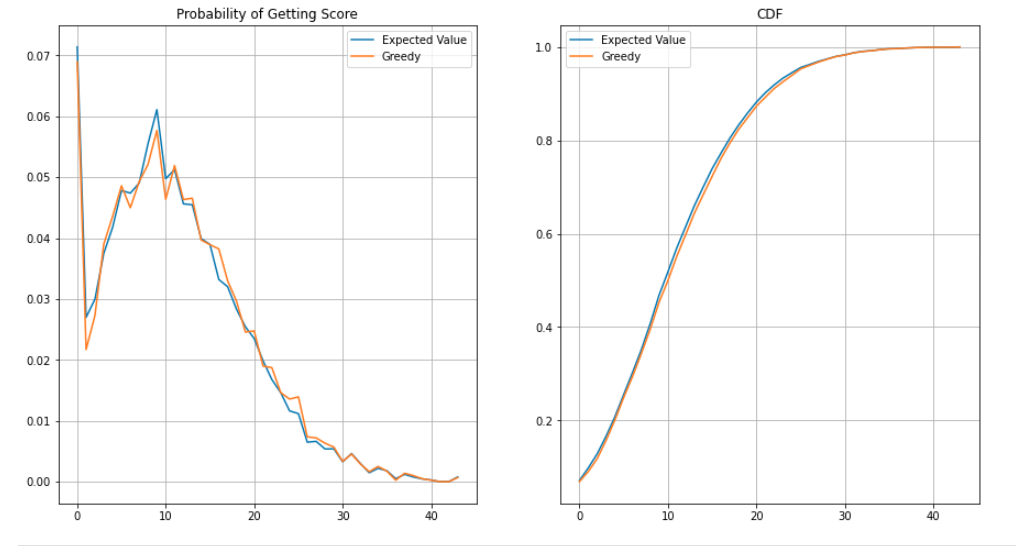

Overlaying the probability distributions leads to small differences, but they could simply be sampling errors.

Viewing their probability distribution functions and cumulative distribution functions has similar conclusions.

However a one sided KS test shows statistically significant differences in their distributions.

from scipy.stats import kstest

kstest(games_played_ev, games_played_greedy, alternative='greater')

KstestResult(statistic=0.018660000000000065, pvalue=7.412305228600443e-16)

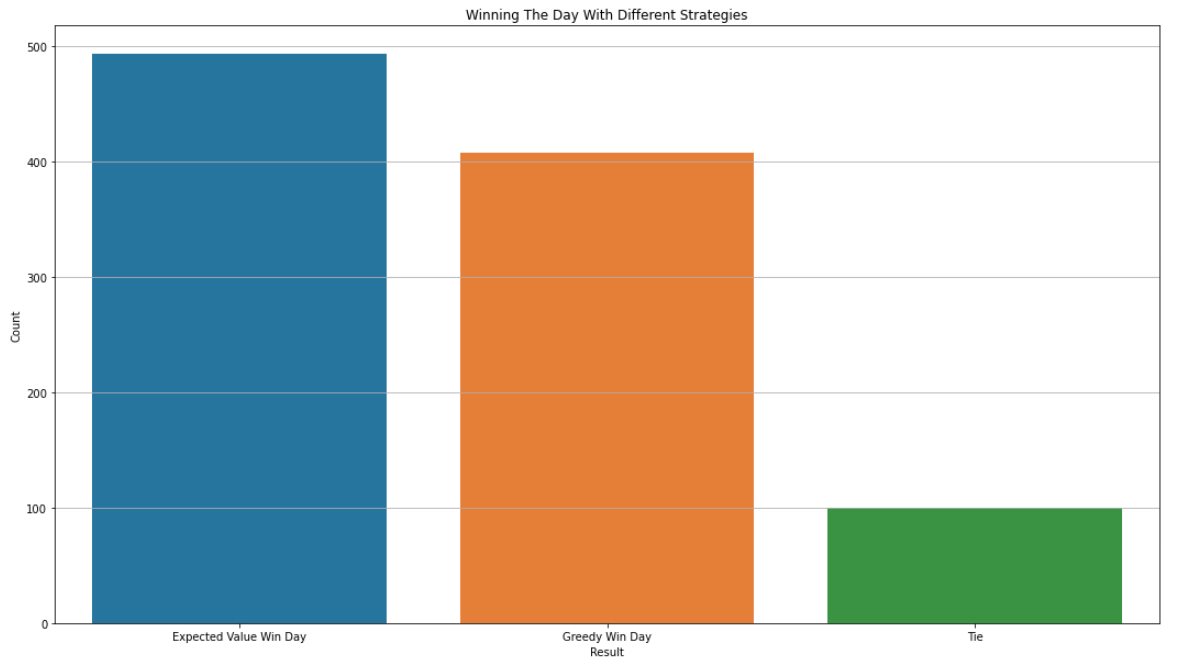

The longer you play though the more the small differences start to matter. We can say a day of playing this game is around 20 rounds. How much does this difference in policy effect the likelihood of winning any given day?

import numpy as np

num_wins = []

num_losses = []

day_results = []

for i in range(1_000):

ev_scores = np.random.choice(games_played_ev, size=20)

greedy_scores = np.random.choice(games_played_greedy, size=20)

wins = np.sum(ev_scores < greedy_scores)

losses = np.sum(ev_scores > greedy_scores)

num_losses.append(losses)

num_wins.append(wins)

if wins > losses:

day_results.append('win')

if losses > wins:

day_results.append('loss')

if losses == wins:

day_results.append('tie')

day_results = np.array(day_results)

table = [

['Expected Value Win Day', len(np.where(day_results=='win')[0])],

['Greedy Win Day', len(np.where(day_results=='loss')[0])],

['Tie', len(np.where(day_results=='tie')[0])]

]

plt_df = pd.DataFrame(table)

plt.figure(figsize=(18,10))

plt.grid()

plt.title("Winning The Day With Different Strategies")

plt_df.columns=['Result', 'Count']

sns.barplot(data=plt_df, x='Result', y='Count')

| Result | Count |

|---|---|

| Expected Value Win Day | 493 |

| Greedy Win Day | 407 |

| Tie | 100 |

This difference in strategy means winning ~9% more days than just playing greedily. Not so small a difference after all!

What is the value of going second in a two player game?

This is slightly a harder question to answer. In order to do this we have to make a couple of assumptions.

- The first player to roll plays optimally for expected value number of points.

- I believe this is not the optimal strategy to win in a two player game

- A simple thought experiment for a 100 person game shows that it probably is not the best strategy, one should be more risky in an attempt to get a good score.

We can represent this difference in policy by calculating the difference in win, loss and tie rate between an expected value player playing against themselves, vs playing an optimized player 2 player knowing what score they have to beat.

class P2Policy(object):

def __init__(self, to_beat):

self.to_beat = to_beat

self.memoize_win_prob = {}

self.wins = None

self.losses = None

self.ties = None

def create_policy(self):

full_board = tuple([1 for x in range(1,10)])

return self._dfs_win_prob(full_board, 0, self.to_beat)

def _dfs_win_prob(self, tiles, roll, to_beat):

if (tiles, roll) in self.memoize_win_prob:

return self.memoize_win_prob[(tiles, roll)]

if roll == 0:

total = 0

for my_roll, prob in dice_probs.items():

total += self._dfs_win_prob(tiles, my_roll, to_beat) * prob

memoize[(tiles, roll)] = total

return total

best_score = -1

for move in get_valid_moves(tiles, roll):

new_tiles = flip_tiles(move, tiles)

roll_score = self._dfs_win_prob(new_tiles, 0, to_beat)

if roll_score > best_score:

best_score = roll_score

if best_score == -1:

best_score = float(score_tiles(tiles) <= to_beat)

self.memoize_win_prob[(tiles, roll)] = best_score

return best_score

def get_stats(self):

if self.wins is not None:

return self.wins / 10_000, self.losses / 10_000, self.ties / 10_000

wins, losses, ties = 0, 0, 0

for i in range(10_000):

result = self.simulate()

if result < self.to_beat:

wins += 1

if result > self.to_beat:

losses += 1

if result == self.to_beat:

ties += 1

self.wins, self.losses, self.ties = wins, losses, ties

return wins / 10_000, losses / 10_000, ties / 10_000

def get_move_best(self, board_state, possible_moves):

best_score = -1

best_move = None

for move in possible_moves:

new_tiles = flip_tiles(move, board_state)

roll_score = self._dfs_win_prob(new_tiles, 0, self.to_beat)

if roll_score > best_score:

best_score = roll_score

best_move = move

return best_move

def simulate(self):

my_tiles = tuple([1 for x in range(1,10)])

while True:

d1, d2 = random.randint(1,6), random.randint(1,6)

possible_moves = get_valid_moves(my_tiles, d1+d2)

if len(possible_moves) == 0:

return score_tiles(my_tiles)

move = self.get_move_best(my_tiles, possible_moves)

my_tiles = flip_tiles(move, my_tiles)

# Calculate the PDF of expected value scores

expected_value_score_pdf = []

for i in range(0, max(games_played_ev)+1):

my_games = len([x for x in games_played_ev if x == i])

expected_value_score_pdf.append(my_games/len(games_played_ev))

# Caculate the win, loss, draw rate of P2

total_win, total_loss, total_tie = 0, 0, 0

policies = []

for i in range(0, max(games_played_ev)+1):

if i % 5 == 0:

print(f"Calculating Policy for {i}")

policy = P2Policy(i)

policies.append(policy)

w, l, t = policy.get_stats()

prob_of_case = expected_value_score_pdf[i]

total_win += w * prob_of_case

total_loss += l * prob_of_case

total_tie += t * prob_of_case

print(total_win, total_loss, total_tie)

# Calculate Self Interactions

size=1_000_000

g1 = np.random.choice(games_played_ev, size=size)

g2 = np.random.choice(games_played_ev, size=size)

self_wins = len(np.where(g1 > g2)[0])

self_loss = len(np.where(g1 < g2)[0])

self_tie = len(np.where(g1 == g2)[0])

print(self_wins / size, self_loss / size, self_tie / size)

0.477316, 0.477553, 0.045129

0.479137, 0.479201, 0.041662

These values are within sampling error. The value of going second is either zero or small enough to be not accurately sampled using the methods above. This is a surprising result! An explanation for this is there is no such thing as a “risky” move, that is a move with higher variance or better extreme value but with worse expected value. We could further compare the actual policies generated instead of the end game results sampled. We could also explicitly calculate the tie, win and loss percentages for a given p2 strategy instead of sampling it. However, to remove all the sampling error we would have to explicitly calculate the optimal expected strategy points probability distribution function also.

This was an interesting game to study, simple enough to calculate explicit solutions and perfectly solve, yet intricate enough to have some novel strategy. It would be fun to hook up ReBel to play around with the codebase. I’m not sure if the method can work with stocastic environments though. If you want to look through the full jupyter notebook analysis it is on my github.